Reporter: Claudia Villalobos | Photographer: Javier González

The researcher is an expert in solid-state physics and has trained generations of high-level students.

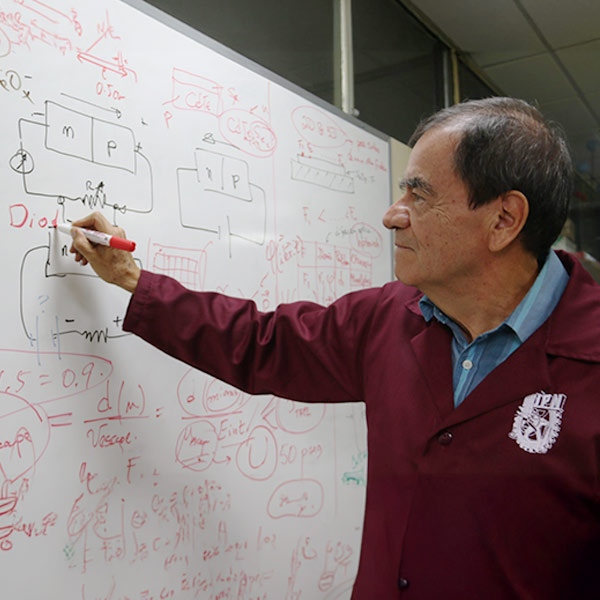

“I tried to share with my students encouragement, joy, and optimism through teaching, but I also enjoy learning from them.”

A small office on the upper floor of the Advanced Physics building at the Escuela Superior de Física y Matemáticas (ESFM) now witnesses the closing of an academic circle of teaching and research. After 52 years, Dr. Gerardo Silverio Contreras Puente bids farewell to the Instituto Politécnico Nacional (IPN).

The office contains a simple desk, shelves filled with books, family and institutional photographs, self-designed equipment, and a whiteboard—now covered with equations, formulas, and notes—where the researcher has shared knowledge, ideas, and lessons over decades.

—After so many years at this school, what are your feelings as you retire?

“It´s bittersweet. Sadness because I am leaving behind a lifetime of work, but joy because I helped shape valuable people and contributed to building infrastructure. What I hope remains is the spirit, optimism, and encouragement I passed on to my students so they could move forward.

At the same time, I am happy to begin a new stage of life; I am, so to speak, in the ninth inning, the last quarter, the penalty shootout of my life. My purpose now is to enjoy time with my family—my wife, children, and grandchildren.”

—Dr. Contreras, you have completed 52 years of service at IPN, but 60 years as a Politécnico.

“Yes, in 1965, I entered Prevocacional No. 4 in Tlatelolco. I lived in the Lindavista neighborhood and took the trolleybus that dropped me off at the intersection of Niño Perdido Avenue and Manuel González Avenue—what is now Eje Central Lázaro Cárdenas.”

“Since elementary school, I have been interested in science. We organized exhibitions where we presented experiments in physics, chemistry, and biology. The prevocacionales had a stronger academic level than other secondary schools, which is why I chose the Politécnico.

I had excellent teachers, some of whom were military officers, while others were ESFM graduates. That’s where I received rigorous academic training and also learned technical skills, such as electrical work.”

“Later, I went on to Vocacional No. 3, located on Avenida de los Maestros and Calzada de los Gallos, where I also received excellent training at the upper secondary level and gained technical experience in electronics.”

—Why did you decide to study at ESFM if you also had the profile to enter the Escuela Superior de Ingeniería Mecánica y Eléctrica (ESIME)?

“My mother was among the first women to graduate as a pharmaceutical chemist from UNAM, at the Faculty of Physical and Mathematical Sciences of the National School of Chemistry. Her example inspired me to enter ESFM, an excellent school for science at IPN. There were also practical reasons: Ciudad Universitaria was far away, but ESFM was only five minutes from home.”

—Did you begin working at the Institute while still an undergraduate?

“That’s right. In my third year of studies, I was hired, and from the start, I loved teaching. Back then, I worked as a problem instructor—not to create problems, but to help professors by solving exercises on the board with students. For example, if a class lasted six hours, four were dedicated to theory and two to solving problems. I also taught experimental physics labs.”

—What do you enjoy most about teaching?

“I like sharing my knowledge with others. I try to give students energy, joy, and optimism to keep moving forward, but I also learn from them.”

“When I was in graduate school, we used a standard classical mechanics textbook, but I discovered a smaller Soviet book that contained more material, so I was always ahead.

Sometimes professors were upset that I already knew the answers, but I never take that attitude with my students. I encourage them to express themselves. If I make a mistake, I correct it, because a teacher should not be seen as sacred but as a flexible guide who allows students to participate and ensures classes are engaging, enjoyable, and collaborative.”

—Where did you complete your master’s and doctoral studies?

“I completed my master’s degree at ESFM. From 1981 to 1985, I was supported by IPN and received a DAAD fellowship to pursue doctoral studies at the University of Stuttgart and the Max Planck Institute for Solid State Research in Germany, under the supervision of Dr. Manuel Cardona. After finishing, I returned to Mexico to continue teaching and research.”

—Have there been moments when your students have surpassed you?

“After 52 years, I can see how quickly science and technology evolve. We now have many laboratories, and it is essential to keep students motivated, because they are the new generations who will take our place and must surpass their teachers.”

“Climbing the mountain is difficult—young people may stumble often—but that is part of the experience that will help them achieve their goals. Their contribution as professionals in the hard sciences, such as physics and mathematics, is invaluable. They must not lose heart, no matter how difficult the path may seem. They must keep their sense of wonder, because only then will they reach the summit. I know they will be successful.”

—Have your students gone on to teaching or research careers?

“Yes, of course. Several of my colleagues in the Solid-State Physics Research Group began as my students, including Dr. Miguel Tufiño Velázquez, whose thesis I supervised. I also contributed to the training of Drs. Jorge Ricardo Aguilar Hernández, Concepción Mejía García, Jorge Sastré Hernández, Rogelio Mendoza Pérez, Adolfo Escamilla Esquivel, and many others.”

“I still supervise students’ theses at the bachelor’s, master’s, doctoral, and postdoctoral levels. Many of my former students have gone on to establish their own research groups in other institutions. They’re like seeds that have taken root and flourished in many places.”

—As the leader of ESFM’s Solid-State Physics Research Group, who influenced you most in this field?

“I owe great respect and gratitude to Dr. Feliciano Sánchez Sinencio, who worked here in the 1960s and founded our research group. He was the driving force behind it, along with colleagues such as Drs. José Antonio Irán Díaz Góngora, Jaime González Basurto, Modesto Cárdenas, Helio Altamirano, and Rolando Jiménez. I was part of the third generation to join the group, which grew significantly and helped spread solid-state knowledge.”

—What do you consider your main legacy?

“Without a doubt, the training of students with whom I shared my knowledge—those who became bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral graduates, whose work has borne the fruit of excellence. Also, my contributions through research projects.

I am the author of four patents, with one more in the process of registration. During the pandemic, we developed a short-wave ultraviolet (UVC) device to inactivate SARS-CoV-2, which is currently operating at Hospital Juárez in Mexico City under the coordination of Dr. Juan Manuel Bello López. I also converted a gasoline-powered car into an electric one as a personal initiative.”

The researcher has authored more than 200 articles and several patents, but hopes to be remembered simply as “a professor named Contreras once passed through here.”

—You have contributed as a teacher, researcher, and administrator. How would you like to be remembered by your students and colleagues?

“Just that—a professor named Contreras once passed through here,” he replies, with emotion in his voice and a gaze full of light and nostalgia.

“I am Politécnico at heart. I inherited the desire to give from my parents. My mother owned a pharmacy, and I was told she often gave medicine to those in need. The actions of my aunts and uncles also inspired me to give without expecting anything in return.”

Now closing a chapter in his life, Dr. Contreras—who had the honor of meeting at least 20 Nobel laureates—looks with pride at the thesis of his mother, Cecilia Puente Cermeño, who passed away when he was only three years old, but from whom he inherited a love of knowledge.

Thus ends the interview with a man who, as a child playing with toy planes and marbles, never imagined he would become an Investigador Emérito of the Sistema Nacional de Investigadoras e Investigadores (SNII), or that he would bring such prestige to the Instituto Politécnico Nacional through his lasting legacy in solid-state physics.